Tupac’s Escape Plan: An Ode to the Bishop of Juice

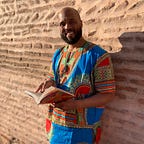

Greg Corbin is a visionary leader who works at the intersection of art, science and equity. He is the author of Breathing Ashes: A Poetic Guide to Walking Through the Fire and Coming Out Reborn. Please feel free to share with your network and leave some feedback. Enjoy!

Sources close to Tupac remarked, in response to his demeanor post-dropbox, “After playing the role of Bishop in the 1992 urban smash hit [Juice], he was never the same.” ₃

Tupac was one of the most gifted artists of our time. He was deeply invested in the state of humanity, and particularly compassionate towards the unfortunate predicaments of marginalized people of color. He understood the psyche of the human condition so clearly that he created a powerful acronym, by which he lived his personal and professional life:

T.H.U.G.L.I.F.E (The Hate You Give Little Infants F*** Everyone). ₄

In the early 90’s many would see the emergence of a thought provoking, charismatic, talented hip hop artist, poet, background dancer, and actor named Tupac Shakur. With a deeply educated mind, trauma filled upbringing he spoke from an experience that many could find a connection with. There was no one like Tupac. The first song I heard from him was Brenda’s Got A Baby, in which he delicately and methodically shares a story of a pre-teen pregnancy. The video debuted on BET in 1992 and is still a startling reminder of his abilities as an artist to convey such truth. It was Black and White. It was done in the urban area of a city, with Ethel Love as Brenda and directed by Allan Hughes.

The video was purposely organized in a way to give the viewer the grimy feel of a gutter laced area hit by socioeconomic challenges. I can easily say watching Brenda’s Got A Baby was one of my first times experiencing an emotional contagion that art can bring to its audience. I felt Brenda’s fear, not just lyrically, but visually. Tupac’s rigorously detailed expression, created a storytelling experience that was hard to find in Hip Hop at the time. In other words “I felt that shit.”

A flexible, risk taking thinker, boldly open minded, Tupac was lyrically direct with his ever stinging critique of politics and its impact on everyday people.

- He was a melanin filled container for the emotion of those abandoned by a social system, built on their backs, and with their hands. He carried the pity, repressed rage, jubilant joy of survival, curiosity of intelligence, mounted frustration, undying love, triumphant confidence of people who looked just like him.

- He was a full expression of the human complexities absorbed from his many walks of life. Internalizing the energy of Baltimore and Oakland, mixed with an Islamic background, while soaking in the ideology of Black Nationalism, Tupac was ever courageous to say what he felt with his full heart and soul. Even if some people didn’t agree, he always seemed to be fully alive and immersed in what he spoke.

- He embodied so much passion. Passion, derived from the Latin word passio, meaning suffering is a perfect word to describe this artist to the core. Tupac was relentless both in the studio and with a movie script. In some ways he seemed tormented from having a high level of intelligence, witnessing many social ills bring pain to his communities.

- He cared deeply for those left in un-nurtured and isolated due to the haunting systemic oppression of marginalized people from many walks. Some may say he had compassion fatigue and needed a constant cathartic release from carrying the full scope and comprehension of the people’s pain. From top to bottom, he understood the impact of poverty, inequality and injustice. He was known to do 7 songs a day when he was in the midst of recording.

So in 1992 when Tupac Shakur played Bishop in the movie Juice he’s at a pivotal and prolific point in his career.

As a high school teenager, Bishop falls in lust with the unrelenting power of a gun.

Unfortunately, after a botched robbery he kills someone. After police interrogate the friends over the incident Bishop still craves for the commitment of his friends, but nothing is the same. This leads Bishop into a dark space of grief and control seeking behaviors. Feeling betrayed by the severed friendships, he eventually spreads rumors about one of the crew members by pinning the murders on him, and plans to kill the friends. The movie ends with a tussle between former friend Q played by Omar Epps. Q in a last chance effort fails to save Bishop who falls to his death. Many believe that Tupac was never the same after absorbing and performing the role of Bishop. Although the character died in the movie, it’s possible Tupac kept the character alive, never fully releasing the remnants of such a troubled person, which could have fragmented his psychological makeup. Bishop is known for the famous line in which he stands by a locker and says to Q, “You think I’m crazy. I am crazy and I don’t give a fuck. I don’t give a fuck about you. I don’t even give fuck about my damn self.”

With this groundbreaking role, Tupac developed a similar edge, internalizing the fears manifested from urban environments that leave young children in predicaments where neglect and needs not being met is second nature. We see the pattern of accountability seemingly always falling on those raised in problematic ecosystems that do not foster whole people, but thrive on the brokenness of those who internalize and cultivate negative behaviors as survival mechanisms and responses to being rendered disposed or invaluable.

We have been conditioned to place blame on the body performing the act and not the system. If cancer develops in a body from smoking do you blame the person or the cigarette? Do you blame the previous generations who knew not of its dangers or do you place blame on the stressors that need to be numbed by a habit or addiction of relief ? Do you place blame on those who make their money off of the cigarettes or do you blame people for not being strong enough to get rid of the habit? Most likely you place blame on the person inhaling 15 cigarettes a day, striving for relief, because unhealthy points of release and self care are celebrated in this country, which feeds on pain, suffering and brokenness.

We live in a country/society that is founded on snatching land from people and objectifying brown bodies for free labor. This country is founded on spiritual brokenness, cognitive dissonance, greed, and acts of immoral insanity that is rendered justified by History textbooks to upkeep a narrative of power. Bishop was looking for power. Tupac was looking for power. They are both searching for balance in a disharmonious society that continuously takes from their contributions, while constantly making them the enemy of state.

Additionally, the role of Bishop amplified the ever growing legend of Tupac. Sourced from a real place, he energetically carried the character with such electricity, ferocity, and pure intensity that it was hard to ignore the impact.

On April 11th, 1992 almost 4 months after Juice made its debut, while high on cocaine and cannabis, Ronald Ray Howard would shoot a Texas State Trooper in the neck after being pulled over for a broken headlight. He would later say he was conditioned by rap music to hate police. His lawyer would use this for defense and cite that Tupac’s Soulja Story incited Ronald to kill. On September 22nd, 1992 Dan Quayle would make the statement, “2Pacalypse Now, has no place in our society.”

When Quayle made that comment, what many heard was not only did Tupac’s voice not matter, but anyone in bodies laced with melanin who had similar stories did not matter as well. It underscored a belief that these voices and experiences were not welcomed in the public eye and must remain trapped in impoverished and disenfranchised environments, silenced in their suffering. Tupac ambitiously seized his material from personal experiences, news stories, and witnessing other’s experiences, therefore Quayle’s words were a full out expression of cognitive dissonance connected to a political agenda deeply tied to controlling cultural exposure and impact. Especially when the vessels for these stories were encased in Black and Brown bodies.

Yes, there was a former Vice President that would say that aloud in a country built on violence and conflict. Tupac literally grabbed his material from his personal experiences, news stories, and witnessing others experiences. Ernest Dickerson’s well-crafted Bishop wasn’t a falsehood in society. It was a genuine and raw expression of the truth. It didn’t just create a criminal, it humanized one, providing the looking glass for the audience to see how people are manufactured by their surroundings and levels of exposure.

One would argue that the former Republican Party VP was using 2Pac as an opportunity to build a political platform for his own run at the presidency. Another argument one could use is that he’s right: Responses to systemic oppression that are cultivated by the lack of opportunity, lack of equity across the board do not belong in our society. Job creation, better schools, etc., belong in our society. Once again citing the symptom through the body of Black Men and not deeply engaging and exploring the symptoms in the ecosystem that create the response. Our argument is that Quayle is saying there is no room for your story in society, and your experience is the America we don’t want to acknowledge, therefore we need to ignore you because you remind us of our own cognitive dissonance and conflicts between morality and responsibility.

Tupac was an artist searching for refuge in the chair of a therapist that he didn’t know existed. It’s challenging to identify a practice that isn’t practiced in the community you reside in. If only mental health was an established practice in communities of color. Art is a needs assessment. And Tupac needed an escape plan. Tupac also needed a supportive inner circle and family that would hold him accountable to him being his best self. The best version of himself. He didn’t have an escape plan and many people outside of art don’t have one either.

Greg Corbin II is an award-winning poet and educator serving over 50,000 change-makers world-wide. He is the author of Breathing Ashes: A Poetic Guide to Walking Through the Fire and Coming Out Reborn, delves deep into topics such as masculinity, human development, art as activism, the importance of self-awareness and self-care and creating a culture of redemption and forgiveness. In this book, Corbin shares an intimate look into the mind of a mental health advocate, taking you through his personal journey with grace, ease, and vulnerability. Each written piece guides you along a path of internal self-reflection and connection and invites you to explore and expand your personal perspective on these societal ills. Purchase Breathing Ashes today.